Alfred Russel Wallace, the Wallace Line, and My Beef with Darwin Getting All the Credit

Let me get this out of the way: I don’t hate Charles Darwin.

If we met over tea, I’d probably ask about his Galápagos trip, compliment his bird drawings, and try not to stare at the beard that could double as a squirrel habitat.

But I do have an ongoing, long-simmering irritation that Darwin’s name is practically synonymous with the theory of evolution by natural selection, while Alfred Russel Wallace who independently came up with the exact same idea is treated like a historical footnote.

And it’s not just about the theory of evolution.

Wallace also gave us one of the most fascinating biological concepts in the world: the Wallace Line, a literal invisible border between Asia and Australasia that slices through Indonesia’s islands like nature’s own VIP rope.

So buckle up, because we’re about to dive into Wallace’s story, the science, my personal travels across this invisible line, and the many reasons I’ll keep banging the “give Wallace his due” drum.

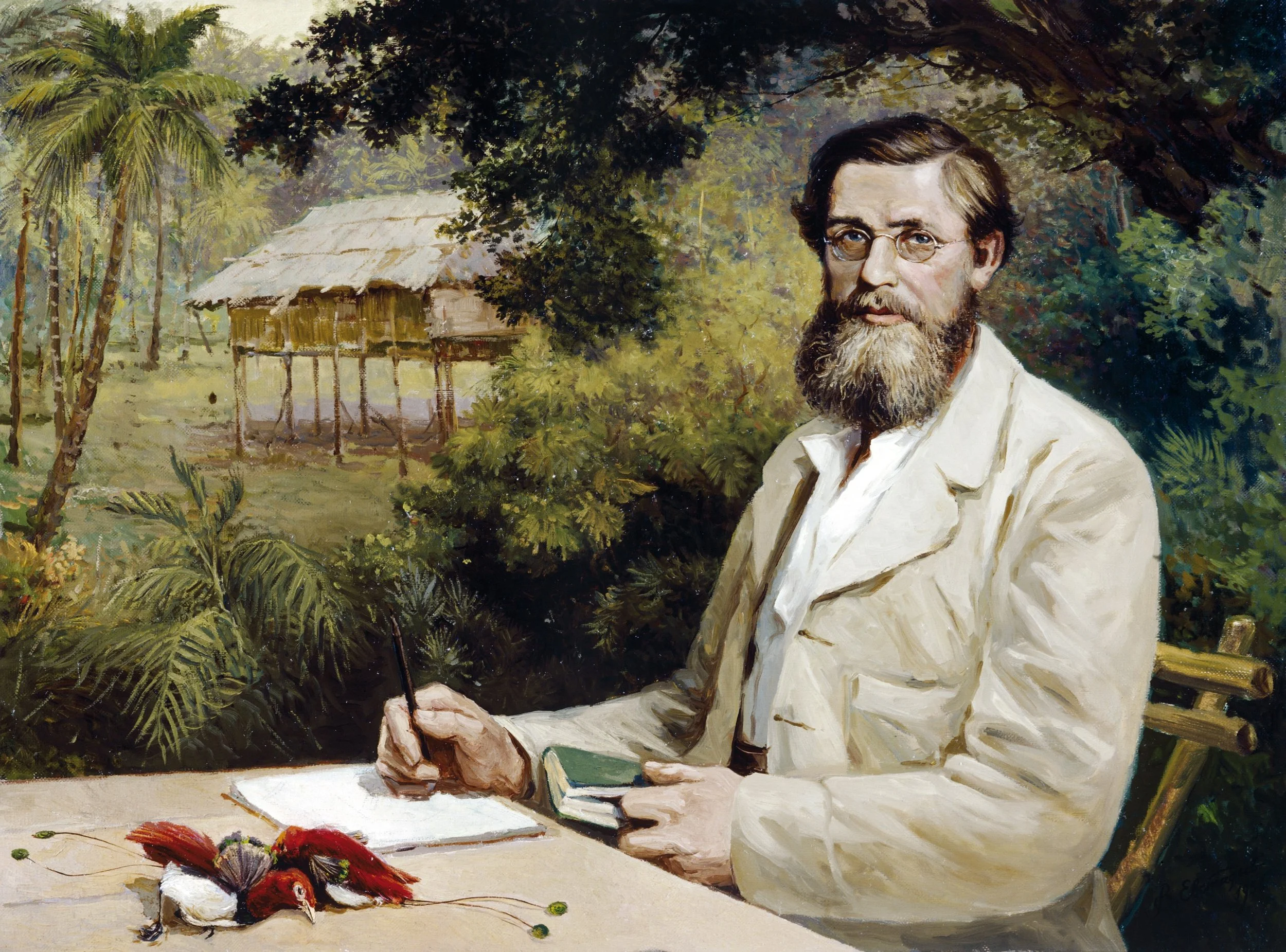

Meet Alfred Russel Wallace

Wallace was born in 1823 in Usk, Wales without the privilege, trust fund, or elite university connections that made so many Victorian scientists possible (looking at you, Darwin!).

After a stint as a surveyor, he taught himself natural history, got hooked on collecting beetles (as one does), and decided to fund an expedition to South America by selling exotic specimens to wealthy collectors back home.

Think 19th-century Etsy shop, but with more mosquitoes and fewer refunds.

His South American adventure ended with a fiery shipwreck that sent his hard-won collections to the bottom of the Atlantic.

Lesser mortals (me) would have called it quits.

Wallace instead decided to try again, this time aiming for Southeast Asia.

This Wallace fangirl standing happily and proudly in front of Wallace’s statue in Tangkoko Nature Reserve in North Sulawesi, Indonesia

Wallace in the Malay Archipelago

In 1854, Wallace landed in Singapore and began what would become an epic eight-year journey through the Malay Archipelago (modern-day Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, and East Timor).

Armed with a butterfly net, notebooks, and what I can only assume was a dangerously high tolerance for tropical fevers, Wallace traveled from the rainforests of Borneo to the volcanoes of the Moluccas.

He documented birds of paradise with feathers so extravagant they looked fake, discovered countless insect species, and made meticulous notes on the distribution of animals across islands.

My Favorite Wallace-Discovered Weirdos

Wallace’s Golden Birdwing Butterfly (Ornithoptera croesus): so rare and beautiful that Victorian collectors went feral for it.

Standardwing Bird of Paradise (Semioptera wallacii): found only in the northern Maluku Islands, rocking two long white plumes like nature’s answer to shoulder pads.

Wallace’s Flying Frog (Rhacophorus nigropalmatus): a tree frog that literally glides from branch to branch like a green pancake with attitude.

I’ve been lucky enough to see Wallace’s Golden Birdwing Butterfly and the Standardwing Bird of Paradise in the wild and yes, I may have cried a little, but in a dignified, nature-documentary kind of way. It’s hard not to get emotional when you’re face-to-face with such rare, living jewels… especially when they don’t seem nearly as impressed to see you.

The Eureka Fever Moment in Ternate

In 1858, while recovering from a malaria bout in Ternate, Alfred Russel Wallace had a flash of insight: species change over time because the individuals best suited to their environment survive and reproduce natural selection.

Like any polite Victorian scientist, he wrote a letter to Darwin explaining his theory.

He didn’t know Darwin had been sitting on the same idea for two decades, tweaking his pigeon breeding and avoiding publication.

Darwin, realizing he might be scooped, had his friends arrange for both Wallace’s paper and his own notes to be presented together at the Linnean Society in London.

History likes to frame this as “two great minds meeting,” but really, it was “two great minds meet, one gets a book deal.”

The Wallace Line

Wallace’s other stroke of genius came from years of meticulous observation. He noticed a striking pattern:

On islands west of a certain line (like Bali, Java, and Borneo), the animals were Asian in character such as tigers, elephants, and woodpeckers.

On islands east of the line (like Lombok, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas), the animals were distinctly Australasian such as marsupials, cockatoos, and giant flightless birds.

This invisible boundary became known as the Wallace Line.

Why It Exists

The Wallace Line marks the point where two ancient continental plates: the Sunda Shelf (part of Asia) and the Sahul Shelf (part of Australia) almost meet, but are separated by deep ocean trenches. Even during the ice ages, when sea levels dropped, those deep waters remained barriers to most species.

Quirky Examples Along the Wallace Line

Bali: woodpeckers galore. Lombok: none at all.

You’ll find cockatoos in the Moluccas but never in Borneo.

Marsupials made it to New Guinea and Sulawesi but never crossed into Java.

Komodo dragons live just west of the line, but marsupials are conspicuously absent there.

My Own Adventures Crossing the Wallace Line

I’ve crossed the Wallace Line more times than Wallace himself (though admittedly with better transport options and fewer tropical fevers).

Bali to Lombok

On one trip, I told guests that when we sailed across the Lombok Strait, we’d be crossing into a new zoological world. They nodded politely… until we got to Lombok and the birds were different, the forests had a different vibe, and the absence of certain species was glaring. Suddenly, it clicked: they weren’t just changing islands, they were crossing a biological border millions of years in the making.

Sulawesi

Sulawesi, the island of oddballs, is east of the Wallace Line and it shows. I’ve met the black crested macaque (with a punk-rock hairstyle that belongs on a ’90s album cover), the maleo bird (which buries its eggs in volcanic sand), and the babirusa (a pig with tusks that curve into its skull, nature clearly got weird here).

Maluku Islands

Sailing through the Maluku Islands, you see cockatoos straight out of Australia, yet you’re nowhere near it. It’s like the continents are playing mix-and-match with their wildlife.

How Wallace Became Personal to Me

Ironically, like many Indonesians before me, I had never even heard of Alfred Russel Wallace until I started working for SeaTrek. It was only then that I discovered not only his role in co-discovering natural selection with Darwin, but also his incredible adventures across the Indonesian archipelago.

SeaTrek even sponsored a children’s book about Wallace, written by Jeni Kardinal, to make his story accessible to young readers, a wonderful way of keeping his legacy alive for the next generation of curious explorers.

And for me personally, what began as a passing introduction soon turned into deep admiration. Endless onboard lectures by passionate experts like George Beccaloni and Ray Hale, who brought Wallace’s observations, quirks, and struggles vividly to life, cemented my fascination. Each talk made me see the islands I was sailing through with new eyes, as if Wallace’s spirit was still perched on deck, notebook in hand.

Why Wallace Still Gets Overlooked

I’ve ranted about this before, but nothing gets me more riled up than when Alfred Russel Wallace gets completely erased from the conversation.

Case in point: I was playing a trivia game at a bar in Bali. The question comes up: “Who came up with the theory of evolution by natural selection?” Now, I’m sitting there thinking, “Ah, finally, my moment to shine!”

But as the answers rolled in: Darwin, Darwin, Darwin, not a single soul mentioned Wallace.

Not even as a joke.

When the quizmaster, my friend Simon (yes, looking at you, Simon), confidently declared “Darwin” as the one and only correct answer, I nearly walked out. We may have had a small quarrel at the bar over it. In fairness, Simon and I have these mini debates all the time but this one? Oh, this one was personal.

Wallace should be as famous as Darwin. But here’s why he isn’t:

Darwin had connections, friends in the Royal Society, access to publishers.

Wallace was humble, he didn’t push for credit, even downplaying his role.

History likes simple stories, “One genius discovers evolution” is tidier than “Two geniuses, one in a tropical fever haze.”

The result? Darwin got the school curriculum, the postage stamps, and the bobbleheads. Wallace got… the occasional nod in a documentary.

Why You Should Care About the Wallace Line

Even if you’re not a wildlife nerd like me, the Wallace Line matters because it’s a living reminder that geography shapes life in profound ways. It also means that Indonesia is one of the most biodiverse countries on Earth, because it sits at the crossroads of two major biological realms.

For travelers, knowing about the Wallace Line turns island-hopping into a layered experience. You’re not just moving from beach to beach; you’re crossing a line that defines where certain species can and cannot exist.

Wallace’s Legacy

In recent years, Wallace has been getting more recognition:

The Alfred Russel Wallace Memorial Fund works to promote his legacy.

Conservation projects in Indonesia reference his work to highlight unique species.

Books like The Malay Archipelago are being rediscovered by new generations of travelers.

But honestly? Until people casually drop “Darwin and Wallace” into conversation, I’ll still be side-eyeing history.

So yes, I have beef with how history remembers Alfred Russel Wallace. He risked his life exploring some of the most remote corners of the planet, independently conceived the theory of evolution by natural selection, and mapped out one of the coolest biogeographical boundaries in the world, all while funding himself through specimen collecting.

The next time you’re in Indonesia, whether you’re diving in Raja Ampat, hiking in Sulawesi, or sailing between Bali and Lombok, remember you might be crossing the same invisible line that blew Wallace’s mind.

Raise a glass to the man who, fever-stricken and deep in the tropics, saw the grand patterns of life on Earth and didn’t get nearly enough credit for it.

And if anyone tries to talk about evolution without mentioning him? Send them my way. I have opinions.

Thank you for reading and now back to happily roaming!